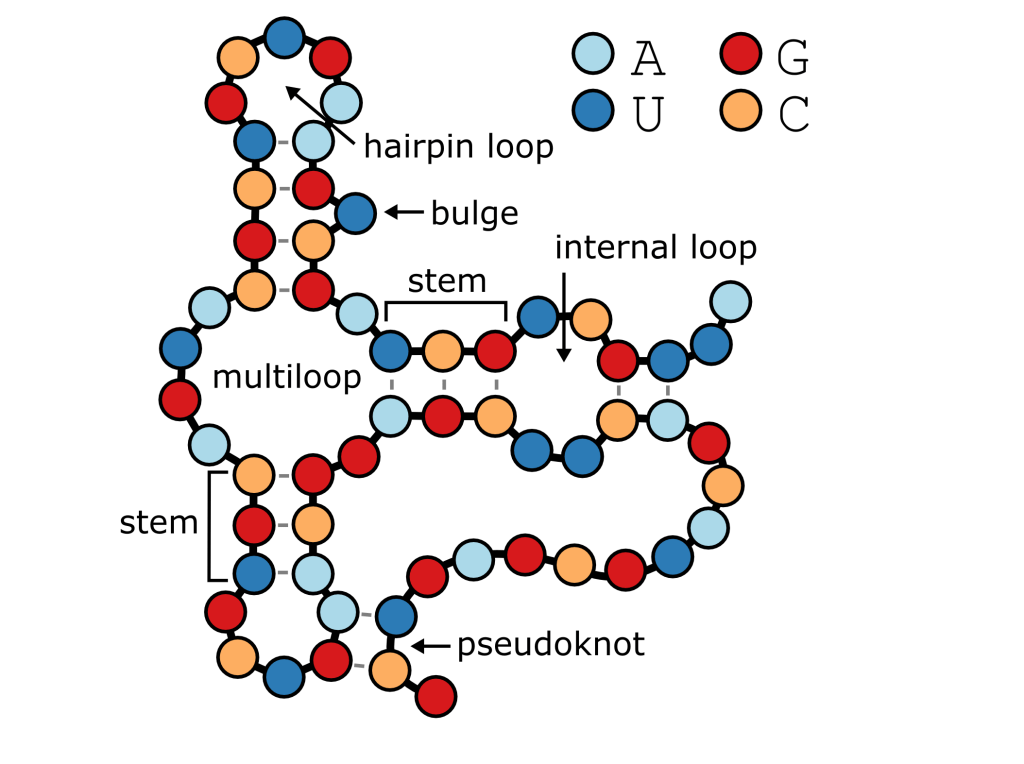

An example of the different possible types of RNA secondary structures. Credit to Oregon State University, sourced from flickr.com under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Most research into epigenetic inheritance – the transmission of traits from cell to cell without altering the DNA sequence – has focused on DNA and histone modifications. New evidence suggests, however, that RNAs, through their complex structures, may transmit information of their own.

If you pull out a biology textbook, it’ll most likely depict an RNA molecule as a straight, 2D piece of string. However, they (like proteins) are able to form complicated structures, such as loops and hairpins.

These “secondary structures” can be altered when a cell is under significant environmental stress, such as heat or lack of nutrients. Importantly, they are reversible upon removal of the stressor.

Chen Cai et al. recently published a comment1 in Nature Cell Biology hypothesising that this ability of RNAs to flip between different structures may be a novel form of epigenetic inheritance.

RNAs aren’t very good at keeping things to themselves

You may have heard of prion diseases, where structural defects in proteins are passed to other “healthy” proteins in the brain, forming large aggregations in and around brain cells which are difficult to clear.

Cai and colleagues suggest that a similar thing occurs with RNA – the stress-induced shapes may form a template which are transferred onto other RNAs via RNA-binding proteins called ribonucleoproteins (RNPs).

These stress-induced RNAs are then inherited by the daughter cells following cell division. The authors propose that RNPs may then “lock” the RNAs in this shape, effectively allowing the new cells to retain a memory of the previous environment, even after the stressor has gone.

This means the new cell will continue to act as though it is under stress, potentially driving misexpression of certain genes and activation of the incorrect signalling pathways, which could lead to pathological cell behaviour. This is particularly relevant for cancer cells, where all sorts of things may go awry with the cells’ internal wiring.

Surely these RNAs can’t last long?

The authors then questioned the evolutionary biology of this. They suggest that because these cells are more attuned to stresses, they may be more prepared to face harsh environments later down the line. In other words, cells containing these wonky RNA conformations may have an evolutionary advantage, outcompeting nearby cells which can’t cope with the stress (which is what occurs in cancers).

However, it may also swing the other way: they mention that cells containing stressed RNAs also tend to grow and divide slower, and therefore may not be able to survive in the long-term. This evolutionary dynamic is something that can be investigated further.

I personally wonder whether there is any in-built cellular defence against these RNA conformations. After all, DNA that’s found to have sneaked out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm is quickly removed by DNase enzymes, so perhaps a similar thing occurs with these oddly-shaped RNAs.

“Yeah, and?”

Ultimately, the authors do stress that this is currently a hypothesis, and that more evidence needs to be collated, such as transcriptomic analyses between stressed and non-stressed cells to see whether having stressed RNAs in the cytoplasm does actually lead to dysregulation of gene expression.

In the RNA field, conformation switching is not a novel idea, and may be involved in some neurodegenerative diseases. The hypothesis that it could be a form of epigenetic inheritance, however, may be controversial: some argue that RNA-mediated processes should not be considered epigenetic (covered in my post here), as they don’t involve chromosomal changes.

I think the ideas in this paper are going to kick up a bit of a storm. Personally, I’m here for it.

Notes

- Comment papers in journals can range from putting forward a new hypothesis to criticisms of previously published research, and often do not contain lots of original data from the authors themselves. ↩︎

Discussion point

What other experiments could we do to investigate whether these stress-induced RNAs are affecting cell behaviour?

Leave a comment