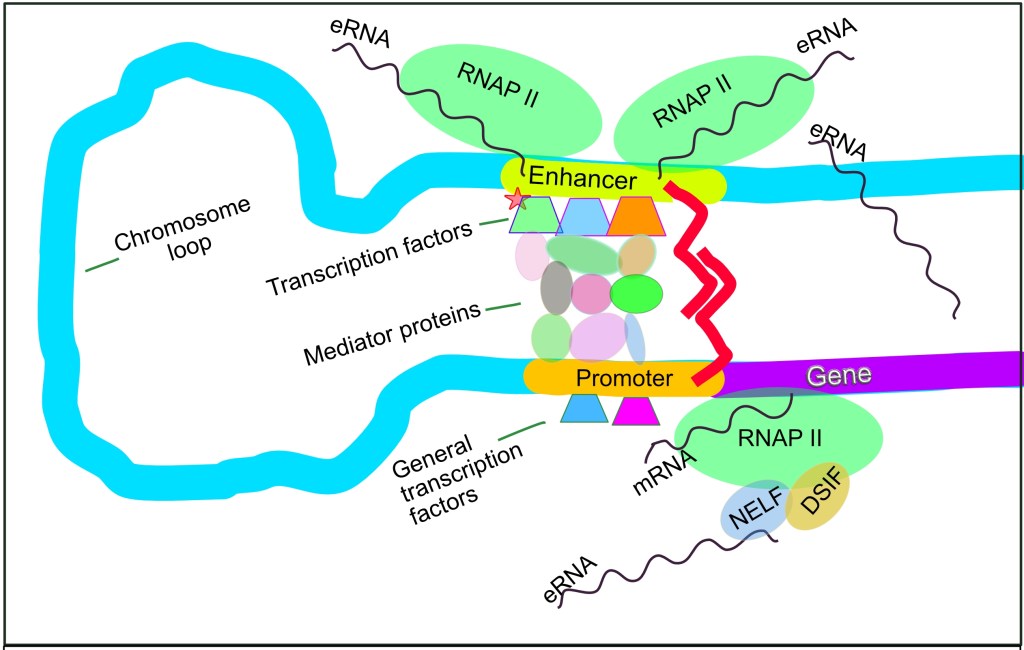

Schematic of transcription regulation in mammalian cells. Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) can be seen being transcribed from enhancers (yellow). Image from Bernstein0275 on Wikipedia, under CC BY-SA 4.0.

I have a confession!

A few months ago, I started a post with the sentence:

“Enhancers are non-coding elements which are littered throughout the mammalian genome.”

– me, 31st July 2025

Turns out I was wrong, because had I checked the (enormous) literature on enhancers LITERALLY 8 days before I published this, I would have come across a totally unexpected finding — that some enhancers are not, in fact, non-coding (i.e., they can produce proteins).

A paper published in Genes and Development by Pavel Vlasov et al. found that a subset of enhancer-derived RNAs contain sequences around 300 nucleotides long which are able to be translated into proteins. NB: this is the kind of paper that will send shock waves through the entire field.

A brief history of transcription at enhancers

The idea that enhancers can be transcribed into RNA is not a new one.

In 2010, a landmark paper in Nature discovered that some enhancers in mouse neurons are bound by the co-activator CBP. This was the first clue to transcriptional activity, as CBP was known to recruit RNA polymerase II (RNAPII), the key enzyme which decodes the genome into messenger RNA.

Using various sequencing techniques, the authors proved that RNAPII was indeed recruited to these sites, and furthermore, that it was actively producing transcripts, and not just sitting there. These transcripts were termed enhancer RNAs (eRNAs).

Biologists were quick to dismiss eRNAs as transcriptional noise. eRNAs are incredibly unstable, don’t have some of the modifications that mature messenger RNAs have (such as a poly A-tail), and are quickly stamped out by the cell’s internal machinery. It was therefore suggested that they were simply a by-product of the chaos that happens during transcription.

eRNAs were once considered to be a result of leaky transcriptional activity in cells. Image from this site, under CC BY-NC 4.0.

However, it then became clear that, despite their short-lived nature, eRNAs did have biological function after all. eRNAs can load factors important for chromatin architecture, such as cohesin, onto DNA, and can even “trap” transcription factors at their target sequences. The most compelling evidence is that using RNA interference to knock eRNAs out (effectively deleting them from the cell) is associated with a drop in enhancer target gene and target protein expression.

But still, the precise roles of eRNAs remained difficult to pin down. A few non-coding RNAs had been found to have the potential to make proteins, but whether this was true for enhancer RNAs was unknown.

Searching for a needle in a haystack

Using computational tools, Vlasov and colleagues searched a database of candidate enhancers to see which contained sequences likely to make proteins. They then performed ribosome sequencing in human cells, which provides a snapshot of all the mRNAs being actively translated. Out of thousands of eRNA transcripts, they identified 53 eRNAs which may be translated into proteins, and focused on the 10 longest of these.

Biochemical analyses found that these 10 sequences (hereafter enhancer open reading frames [eORFs] 1-10) had more arginine residues than the average human proteins, suggesting the proteins were highly basic, i.e. had a high pH, and therefore probably had a strong charge associated with them.

The authors suggested that all these charged arginine residues may be involved in phase separation, essentially separating out the components of the nucleus into their own compartments, however this is something that requires further experiments to answer.1

Part of the eORF4 sequence in Homo sapiens. R = arginine. Adapted from Vlasov et al. 2025, supplementary figure 11.

Validation in vitro

However, computational analyses can’t tell us everything — we need to see whether these proteins are functional inside a living system.

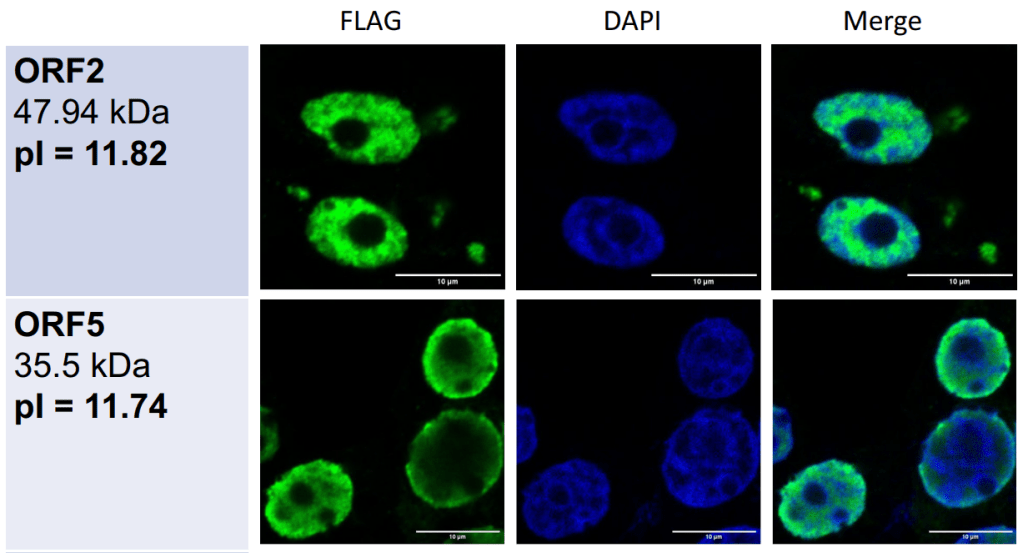

The team generated genomic plasmids (essentially circles of DNA containing the eORF sequences) and added them to human cells to encourage them to produce the 10 proteins with their own ribosomal machinery. Using immunofluorescent tags to show the localisation of each protein, all 10 were found to localise to the nucleus, with some more at the periphery, some at the centre, and some even projecting out from the nucleus.2

The authors commented on the overlap of eORFs with DAPI staining, which stains DNA. However, this is perhaps not the most informative way of looking at subnuclear distribution.3 They therefore physically isolated different components of the nucleus, and found that all 10 eORFs could bind to chromatin using Western blotting, a technique which can detect protein levels in different parts of the cell (and that haunted my undergrad years!).

Subnuclear localisation of 2 eORF proteins. FLAG, tag marking the location of the protein; DAPI, DNA staining. pIs are >11, suggesting these are heavily basic proteins. Adapted from Vlasov et al., figure 3A.

But what about the functionality of these proteins? Using mass spectrometry, which can separate out protein molecules in order of size, the authors found that all 10 eORFs bind to proteins involved in ribosome structure and function. Ribosomes are the machinery in cells that allows mRNA to be translated into protein.

But how are these interactions maintained? Adding RNase — an enzyme that breaks down RNA — blocked these ribosomal/eRNA interactions, suggesting that other RNAs were involved in facilitating these interactions, a little like building a scaffold. This is consistent with the authors’ computational analyses, which predicted that all 10 eORF proteins were found to contain RNA-binding sites.

In addition to RNA, 10 eORFs were also found to bind histones (and in some cases histone modifiers, such as histone deacetylases), the packaging proteins of DNA, which means eORFs could also could be involved in regulating chromatin architecture.

Moreover, these eORF sequences were evolutionarily conserved, but only within primates (such as gorillas and apes), with some features only seen in human RNAs. This suggests that these enhancer-derived proteins only recently evolved these function and that some may even be human-specific, which is quite striking.

Pan troglodytes (chimpanzees): closely related to humans, and one of the species used by the authors to compare the human eORF sequences to. Image from <a href="http://H. Zell, CC BY-SA 3.0 H. Zell via Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0.

“Yeah, and?”

Recent analyses have also suggested that the eRNA landscape in cells can change throughout development, within tissue types, and in cancer cells too. And things are advancing pretty fast; we’re currently investigating whether eRNAs can be used as a biomarker or therapeutic target for breast and pancreatic cancers.

Proteins are generally more stable and therefore easier to detect than eRNAs, so if we could perform similar analyses for the translated eORFs discovered in this study, this could be a huge leap for cancer therapeutics a few years down the line.

Ultimately, this paper is the first to demonstrate that RNAs derived from enhancers can be translated into functional proteins, which themselves may regulate chromatin. It’s yet another layer of epigenetic regulation that could be looked into. And look into it they will, I’m sure!

Notes

- I was wondering whether this would allow them to potentially interact with DNA (which is known to be acidic). However, further computational analyses revealed very few DNA-binding motifs in the translated eORFs, so this is unlikely. ↩︎

- A note on methodology. To be honest, I’m not too convinced about the accuracy of the eORF localisation with immunofluorescence. The antibodies to detect the fluorescent tags on the proteins were only left on for 1 hour, which may not be enough time to fully penetrate the whole nucleus to detected the translated eORFs, especially since the authors mentioned that they were expressed at a similar level to lower-expression-level mRNAs. This would lead to accumulation on the edge of the nucleus, which is what they’re seeing here. However, they added the fluorescent tag to different ends of the eORF protein, and found the same localisation in either case. ↩︎

- In future, if they wanted to do further IF analyses, they could use nuclear lamins/pore/nucleolar markers to see whether there was any colocalisation with the tagged eORF proteins. ↩︎

Discussion point

By what mechanism could these eORF proteins have evolved so recently?

Leave a comment