Artistic rendition of enzymes repairing a DNA break. Image from Flickr.com, courtesy of Tom Ellenberger, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Dave Gohara, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Hi again! I hope everyone had a great Christmas period and New Year. After a few weeks off back at home, I’m excited to be getting stuck into this blog again for 2026.

In my last post, I discussed how chromatin having some sort of “memory” was a really trending topic last year. Recently, a paper came out investigating this in the context of DNA repair. Read on…

DNA Repair 101

Firstly, some background on DNA repair. Our genetic material is not invincible, and receives tens of thousands of hits per day, often caused by external factors, including UV radiation from the sun and high doses of X-rays. In some cases, the damage comes from within our own cells — our mitochondria, for instance, launch out reactive oxygen species that may enter the nucleus and cause DNA to break (though this is debated).

Fortunately, our cells have evolved intricate mechanisms to repair DNA. There are several different paths that a cell can take to fix DNA breakage, some of which are hastier and more prone to mistakes than others.

The sun’s rays contain UV radiation, which can cause DNA damage, in some cases leading to skin cancer. Image from freerangestock.com, licensed under CC0 1.0.

“Chromatin fatigue”

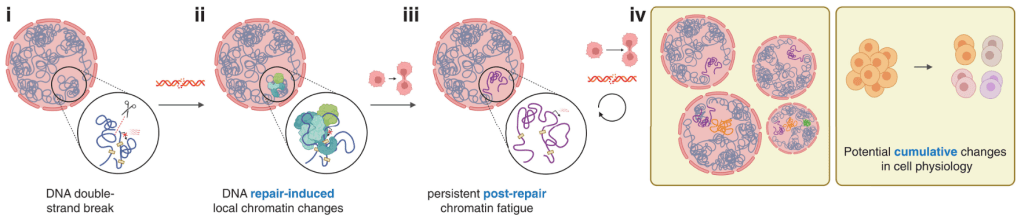

DNA has an intricate 3D looping structure which finetunes which genes are expressed and when. When DNA is in need of fixing, this disrupts these loops — histone packaging proteins are pushed out the way and armies of proteins are shipped in to repair the damaged site.

While the DNA helix itself is often (but not always!) faithfully repaired, whether the 3D loops and folds return to their native conformation has remained underexplored. If it doesn’t return to the way it was before, then this may have lasting consequences on the overall function of the cell.

Susanne Bantele and colleagues at the University of Copenhagen find for the first time that chromatin’s 3D structure doesn’t fully recover after DNA damage, which they term “chromatin fatigue“. Chromatin fatigue can be passed on to daughter cells, which may provide valuable insights in the fields of cancer biology and gene editing.

We’ll cut that site when we get to it

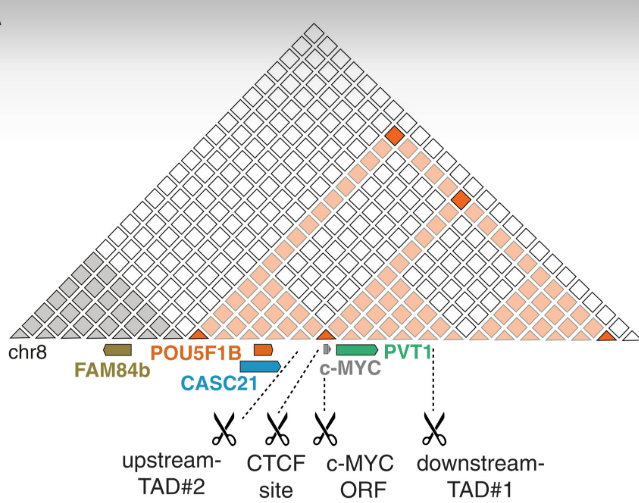

The authors used a CRISPR-Cas9 system1 to cut the DNA in their desired testing place — in this case, a self-contained region (known as a TAD2) containing the c-MYC gene.3

They found that cutting (marked by scissors; see below) throughout this region caused a drop in transcription of the surrounding genes (c-MYC, PVT1, POU5F1B, and CASC21).4 This was not the case for FAM84b (brown) outside the region, showing these effects are strongly localised within the TAD.

But what if this was just the case for a short time, and things went back to normal? The authors looked at c-MYC expression 2 and 5 days after inducing the DNA breaks (ensuring the Cas9 was not still running rampant in the cells cutting unrelated parts of DNA) and found it was still expressed at reduced levels. This suggests that, even though the cut had been repaired, something else was causing c-MYC to be feebly expressed, even in successive generations of cells.

Going no contact

Perhaps the c-MYC TAD was not forming its proper genomic contacts anymore due to the DNA break. To investigate this, they used a technique called Region Capture Micro-C (RCMC), which maps the chromatin folds and contacts within a certain region, in this case, the c-MYC TAD. RCMC has higher resolution (can identify smaller-scale contacts) than traditional techniques like 3C, so it’s suitable for looking at a relatively small region like this.

They found a profound loss of physical interactions within the TAD after cutting the DNA, and this was also transmitted to the daughter cells. They validated this with microscopy, in which you can even see the contacts drifting apart:

Is this a permanent change?

The next step was to assess whether chromatin fatigue could be reversed. The authors tried stimulating c-MYC expression by adding epithelial growth factor (EGF) to the cells to help them grow and divide, and c-MYC expression still didn’t fully recover. This suggests that chromatin fatigue is lasting and not easily reversible.

What’s the mechanism of this fatigue? We’re not entirely sure yet! Maybe it’s because the cell would have to spend lots of energy to return chromatin to its original state and push the nucleosome proteins back to their original spots. Also, there’s no sign that the c-MYC TAD can hold up to signal to the nucleus to say its 3D structure needs an urgent makeover, so it just stays in its post-repair shape.

“Yeah, and?”

This paper is the first to show that DNA breaks have lasting impact on the genome’s 3D structure even after they’re repaired. Moreover, this work may provide insights as to why, in cancer cells where DNA is frequently broken or damaged, there is a persistently altered transcriptional landscape.

Chromatin fatigue is also something to think about for people doing CRISPR/Cas9 experiments, which often rely on inducing DNA breaks in specific genes, as it could have unintended consequences on people’s experimental results.

The authors also validated the phenomenon of chromatin fatigue in other cell lines, including RPE1 non-cancerous human cells. They primarily worked with HeLa cells, a breast cancer cell line, but cancer cells are known to have inefficient DNA repair and funky chromatin structure. So, importantly, the authors also showed chromatin fatigue occurs in physiologically normal cells too.

It’s impressive work that’s clearly taken a lot of time and effort. As I was reading this paper, I was thinking “hmm, maybe they could also do X, and maybe they could do Y”. And then I’d keep reading and a paragraph later it had been done!

Notes

- I do have some questions regarding their validation of whether DNA was actually cut that maybe DNA repair people can help me out with? See “Notes cont’d.” (I didn’t want to write it all here!). ↩︎

- Stands for “topologically associated domain”; essentially a region of DNA that primarily regulates genes within its own boundaries. ↩︎

- The authors did amazingly at ensuring they had appropriate controls. They cut outside the TAD, had a positive control (cutting in the c-MYC locus itself), and used a form of CRISPR-Cas9 that “nicks” DNA (only cuts one strand) as a comparison. One thing I would suggest is that it may have been useful to try with an enzymatically-dead Cas9 protein that can’t cut DNA to ensure any effects on surrounding chromatin structure were due to the cutting of Cas9 and not its binding to the DNA. ↩︎

- In most cases. Some cuts resulted in non-significant changes. ↩︎

Notes cont’d. — technicalities of using 53BP1?

The authors used 53BP1 immunofluorescence as a marker for DNA repair sites to validate that their cut sites were actually cut. I don’t have much background in DNA repair biology beyond what I know from undergrad and what I researched while reading this paper, so if I’ve made a mistake here, let me know, but ultimately, I’m not sure I’m so convinced about their use of this marker. Firstly, it doesn’t bind to DNA itself, so whether 53BP1 is 1) actually chromatin-bound and not simply floating around above breakage sites (especially as they have no DNA staining in their images), and 2) as good a marker as something like γ-H2AX, which is found directly at breakage sites, remain important questions. And secondly, I mentioned above that DNA can be repaired in a variety of ways. 53BP1 is only involved in one of these pathways, called the NHEJ pathway, which is a quick fix method that repairs DNA in around 30 minutes. Choosing 6h and 24h as timepoints to check on chromatin fatigue may therefore have missed out on some of the immediate effects of the break, and also selecting 53BP1 means the study misses out on seeing chromatin fatigue at sites repaired via other, more diligent repair pathways e.g. homologous recombination.

Leave a comment