On the evolution of epigenetics, both as a field and as a term (and my first post!)

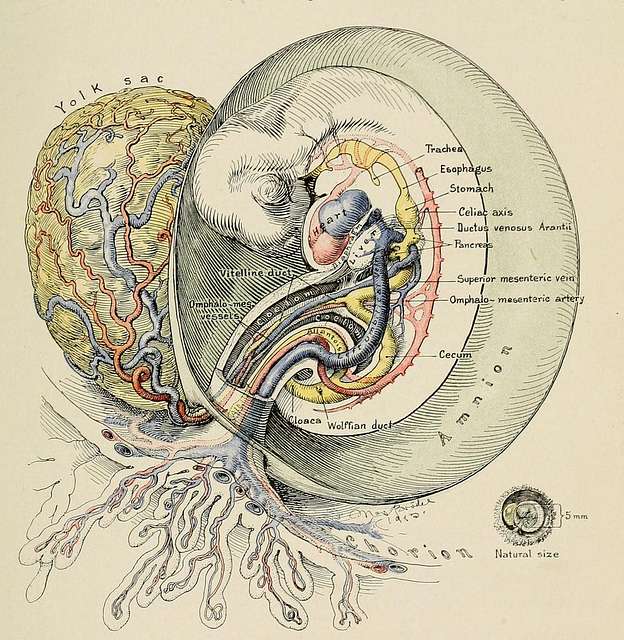

A diagram of a developing human embryo from a 1916 textbook (image is in the public domain).

The meaning of words changes over time. “Awful”, for instance, used to mean “impressive”. Now it means quite the opposite.

“Epigenetics” has not escaped this.

I wasn’t sure how to start this blog initially, but I knew I couldn’t start without writing, in some way, about the history of epigenetics. But instead of listing out all the discoveries made over time, I want to come back to the word “epigenetics” itself, and how and why the field has shifted its definition over the past few decades.

Let’s start at the very beginning

Conrad Waddington, a British developmental biologist, first coined the term “epigenetics” in his seminal 1942 paper, very simply entitled “The Epigenotype” (ah, snappy paper titles, what happened to you?!).

Waddington hypothesised that through investigating an organism’s physical features you can, in combination with genetics (which was still in its infancy back then), unpick how it developed, but regarding how you’d get from genes to physical characteristics, there was a black box – the “gap between genetics and experimental embryology”.

Epigenetics, according to Waddington, was the way of filling this gap.

1942 is a long time ago

In the years since then, people have come up with different definitions for “epigenetics”. I won’t list them all because they’re broadly similar, but here’s one that’s commonly cited:

“the study of changes in gene function that are mitotically and/or meiotically heritable and that do not entail a change in DNA sequence”

Wu and Morris, 2001

So what are the changes?

1. Where did development go?

You may notice this is a more generalised definition; development isn’t mentioned once. This may be because epigenetics has proved itself invaluable in fields outside of development, such as cancer biology.

2. “Changes in DNA sequence”.

With molecular biology practically exploding as a field in the late 20th century, we soon discovered that DNA doesn’t exist naked in a cell; it curls around packaging proteins and interacts with thousands of RNAs, “reader” and “writer” proteins, and a cacophony of other factors to ultimately establish epigenetic marks – the “epigenome”. Over time, we discovered that these factors worked together to fine-tune gene expression whilst leaving the underlying sequence untouched.

It is therefore completely understandable for us to now define epigenetics with DNA and genetics at the centre rather than development.

In 1942, “relatively little” (Waddington’s own words) was known about the way in which a genotype gives rise to a phenotype. This was certainly true enough – the now-familiar double helix structure of DNA wasn’t even known at this point!

Deichmann (2016) nicely summarises this shift as “epigenetics as biochemistry”, compared to Waddington’s definition of “epigenetics as development”.

3. Heritability.

There’s a lot to unpack here. I’ll come back to this.

Is there an agreed definition?

Scientists have sat down and talked for hours and hours over countless cups of coffee trying to come to a consensus definition. One was reached in 2008 at a conference at the Banbury Center in New York, U.S.A.:

‘‘An epigenetic trait is a stably heritable phenotype resulting from changes in a chromosome without alterations in the DNA sequence.’’

Berger et al. 2009

In other words, for something to be “epigenetic”, it has to cause a lasting change in the overall landscape of the genome which can be passed down.

So that’s it? Nope. It’s important to realise that the current definition is not set in stone. Even now, biologists are still arguing about what constitutes an “epigenetic” change.

Some, including myself, would argue that epigenetic traits don’t all result from “changes in a chromosome”. Many non-coding RNAs (which don’t provide instructions for producing proteins, but instead have roles in keeping gene expression in check) work outside of the nucleus entirely AFTER genes have been transcribed, but still are considered to be epigenetic regulators.* Others, however, want RNAs out of the club.

You may also notice that the words “gene function” has been left out of the Banbury definition, whereas it is in the one above. As put nicely in this review, epigenetic modifications are also crucial in regulating parts of the genome that are not genes, such as when permanently shutting down expression of potentially dangerous repetitive DNA sequences.

OK, you said you’d come back to it.

The concept of “heritability” has also stuck. I’ve emboldened it in the two definitions above. This is the part biologists disagree on most.

“Heritable” here means that epigenetic changes can be passed down throughout generations, in the same way that genes are. It’s the idea that “you are what your parents ate”.

There are several groups around the world studying “epigenetic memory” – the transfer of epigenetic marks over generations of cells – including in my own department. This is important for, e.g., ensuring that when a liver cell divides, it retains the same gene expression patterns to make another liver cell, and not something else.

This is all very well and good in cells in a dish, some say, but what about at the level of organisms like us? We know that some environmental factors don’t directly influence the order of As, Ts, Cs, and Gs of the DNA sequence in mice, but instead alter epigenetic modifications and consequently gene expression, which can then be passed down to their offspring.

Whether this happens in humans is incredibly controversial, however, since 1) lots of the epigenetic marks, especially DNA methylation, are erased in early development, so how can they all be passed down?**, and 2) even the tiniest environmental change may change epigenetic modifications, and you DEFINITELY can’t put humans in controlled, identical environments all their lives to study their epigenomes.

I would therefore argue that “heritable” should be clarified to mean “at the level of individual cells” when defining epigenetics to avoid confusion.

So do we need a consensus definition today?

Epigenetics is a hot topic right now, and having a consensus on what it should encompass may prevent people from making exaggerated conclusions, or claiming that anything unexplained by genetics is “epigenetic”.

On the other hand, it’s become such a broad field that defining it in such molecular terms as we do isn’t useful to everyone, such as clinicians, who don’t always need to know about the particular chemical modification on this particular residue of this particular protein.

Finally, it’s important to note that Waddington’s original definition is far from invalid. Indeed, epigenetics (as we know it today) has been instrumental in unravelling what he described as the “concatenations of processes” behind development. In his 1942 paper, Waddington mentions the process of gastrulation, in which part of the developing embryo splits into three distinct cell layers. A brilliant paper published last month mapped some of the marks and modifications underlying the split into these three lineages at the level of single cells.

One last thought. Maybe epigenetics and genetics shouldn’t be so separately defined anyway. After all, they do directly influence each other; the genome has to produce all these proteins that make the epigenetic marks in the first place.

“Yeah, and?”

I’ll end with a note on why I decided to write about this.

Many of my subsequent posts will be about recent articles or discoveries.

It can be easy to become short-sighted or feel despondent about progress in a small, very specialised area, while forgetting how much knowledge we’ve gained since the beginning. I myself am guilty of this sometimes when doing my own experiments.

This article is a reminder to step back and look at the big picture, which I believe is often not done enough in science, and a reminder to, occasionally, go back and read original papers.

Finally, with 2025 being the 120th anniversary of Conrad Waddington’s birth, I feel this is an important time to remember just how much the field has evolved, and how much potential there remains in epigenetics research today.

Notes

*Note, however, that the best-characterised example is the non-coding RNA Xist, which does act at the level of the chromosome by coating the additional X chromosome in female cells to silence it. If Xist didn’t exist (haha) female cells (with 2 X chromosomes, XX) would produce twice as many proteins from the X chromosome as male cells (with only 1 X chromosome, XY), which would be lethal to the cell. This is termed X inactivation.

**Side note: some aren’t, but this would be a massive digression, and this article is already quite long!

Discussion point

Do you think we still need a consensus definition of “epigenetics” in 2025? If so, will we ever reach one? Let me know what you think down below 🙂

Leave a comment