Since it’s coming up to the end of the year, and since Spotify Wrapped came out the other week (despite it saying my listening age was 76!), I thought I’d do my own roundup of 10 exciting and impactful findings in epigenetics and -genomics published in 2025. Here goes!

1. A detailed, single-cell methylation map of the aging mouse brain (Zeng et al., BioRxiv).

DNA methylation involves chemically tagging the genome at specific sites, and this can be used to map aging.

The authors investigated methylation patterns at hundreds of thousands of individual cells in the mouse brain, and found that methylation changes during aging were more pronounced in cells that weren’t neurons, as well as identifying novel age-related structural changes to the genome (particularly at CTCF sites).

This may help us understand age-related neurodegenerative conditions in humans, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

2. Unveiling gene networks in olive plants (Forgione et al., Int J Mol Sci).

Forgione and team identified a network of light-receptive genes in olive trees (an understudied plant model) as well as unveiling a master transcription factor linking light to the plant’s metabolism. This research could help maximise growth for breeding or aid agricultural management strategies for olives and other woody plants. Plus I love olives, so that’s great for me.

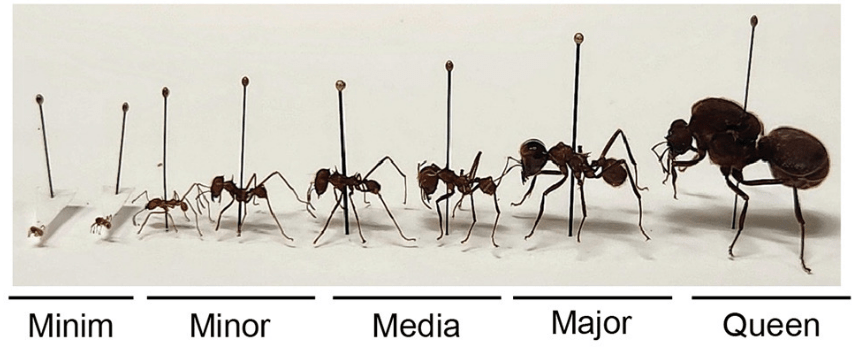

3. Expression of brain proteins defines ants’ jobs within their nest (Gilbert et al., Cell).

The authors studied leafcutter ants, which form distinct “caste systems” in which each ant is adapted differently to help them perform a specific job, such as harvesting leaves or defending the nest.

Proteins in the brain, or neuropeptides, may be involved in defining each ant’s role, and by knocking out or injecting specific neuropeptides, they were able to make the ants switch or lose their roles. This may also have a strong epigenetic component.1

Analyses of gene expression suggested a strong similarity between these ants and eusocial mammals (i.e., those that have highly organised and advanced social systems), specifically the naked mole rat (Google what they look like if you want a laugh).

4. Some enhancers can be translated into proteins (Vlasov et al., Genes Dev).

I was always taught that enhancers are non-coding sequences, which help with regulating gene expression but don’t make proteins themselves, so this paper blew my mind a bit.

Vlasov et al. identified a subset of enhancers which be translated into proteins that may support gene regulation, a few of which are, intriguingly, human-specific. I have covered this more comprehensively here.

5. Tracking chromatin shape during lung cancer progression (Liu et al., Nat Genet).

Liu and colleagues found — in single cells, without disrupting the native structure of lung tissue! — that DNA folds up differently throughout different stages of lung cancer in mice.

These findings help us understand how cancer evolves cell by cell, which may be used to guide diagnoses in future.

6. Removing inappropriately-marked chromatin may help tiny worms’ brains respond normally (Rodriguez et al., PNAS).

One mutant form of Caenorhabditis elegans (a small roundworm often used in genetic manipulation studies), due to inheriting incorrectly methylated chromatin, doesn’t respond to food or other signals in the same way, although their nervous system appears normal.

By switching off this inappropriately-inherited chromatin, the worms begin to respond to food normally. This shows that altering epigenetic marks can change behaviour, even in non-mammalian organisms.

7. Manipulating fear responses in mice through a single promoter (Coda et al., Nat Genet).

The chromatin/behaviour link is clearly trending, because a month later, this paper was published.

Manipulating chromatin in a specific cell type in the brain important for forming memories at just one promoter changed how mice respond to a fearful stimulus. This is proof-of-concept that epigenetic marks have a causal, not just correlative, link to how mice learn and behave. I have covered this more comprehensively here.

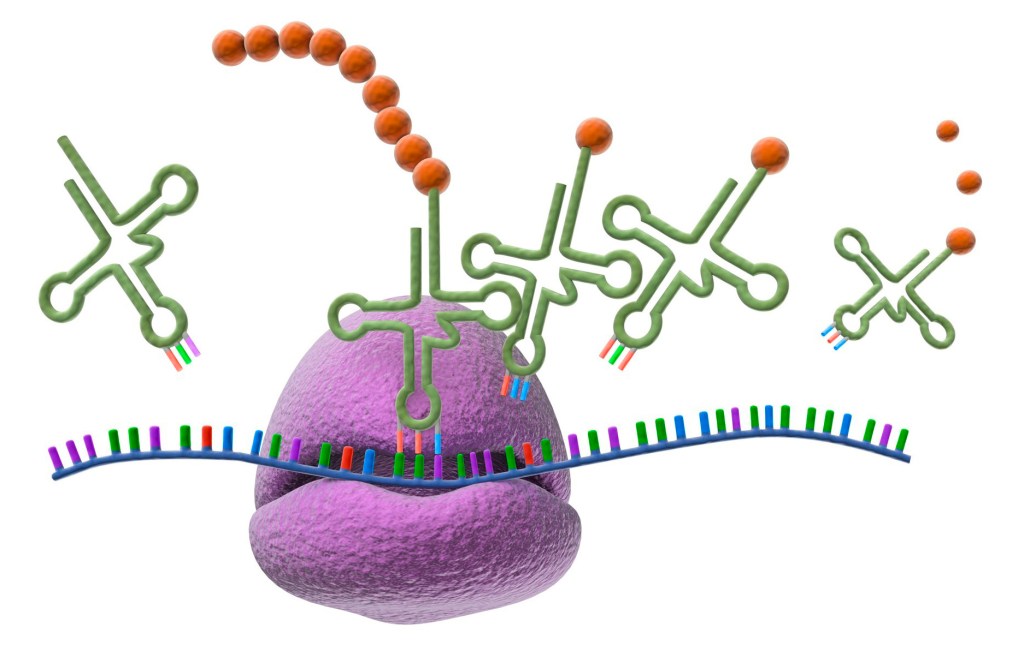

8. Mapping and modelling how the genome connects at base-pair resolution (Li et al., Cell).

Understanding our how our genome forms its 3D shape at high-resolution, while also accounting for biophysical factors and the crowded environment of the nucleus, is a mammoth task.

The authors developed a method called Micro Capture-C ultra, which maps genomic contacts down to single base pairs (A-T, C-G) and found that regions devoid of nucleosomes, which help package DNA into its 3D structure, may be crucial for helping these contacts form.

They were then able to simulate these interactions with computational tools to see how they would look in living cells. You can see how the chromatin structure changes when packaging proteins are removed or modified:

9. Enhancers can be made to reach out further (Bower et al., Nature).

More genomic connectivity work!

Enhancers can connect to sequences many megabases away, but what exactly determines this connection isn’t clear. Bower and colleagues identified a short sequence, which they termed Range Extender (REX), that allowed some enhancers, particularly those involved in limb development, to form longer contacts. When REX was knocked out, this long-range activity stopped, and limbs stopped developing properly. I have covered this more comprehensively here.

10. “Chromatin as a three-dimensional memory machine” (Owen and Mirny, Curr Opin Struct Biol).

Not a research article, but a review/opinion paper on epigenetic memory (thankfully, someone wrote one with all the articles being published at the minute!). This may be the most elegant (and honest; see below) summary of the complexity of chromatin biology I’ve read in a while.

But despite the complexity of this field, they are not pessimistic and instead propose two interesting ideas: 1) that we should look beyond very small-scale models of understanding epigenetic memory, and 2) that chromatin works like a Hopfield network, a type of neural network that learns and then recalls the association between two things (like how a certain smell might make you recall a memory from years ago), to adapt to the environment and re-establish lost modifications.

I hope you enjoyed this list! It seems that epigenetic memory and how chromatin guides behaviour were trending topics this year.

This is likely to be my last post of 2025, as I’m in the middle of writing my MSc(Res) thesis (which is taking up lots of my time), and it’s also Christmas (which is taking up lots of my time, but in a much more fun way ;)).

See you in 2026!

Isabella x

Notes

- I saw this paper presented at a conference in October by Shelley Berger, the paper’s last author, and it was genuinely such a cool presentation that I couldn’t exclude it from this list. More was expanded on the epigenetic component during her presentation, but as this is unpublished I unfortunately can’t expand upon it here. ↩︎

Leave a reply to scrumptiouslyrunawayd84f1024b8 Cancel reply